Credit: iStock/Danielle Griffin

Ishtartv.com

- eos.org

By Mara

Johnson-Groh, 31 December 2019

Records of aurorae in Mesopotamia

from 2,600 years ago are helping astronomers understand and predict solar

activity today.

On a dark spring night, the sky

blanketing the Neo-Assyrian Empire turned red. The “red glow” was taken as an

ominous sign—one important enough that the Assyrian court scribe Issār-šumu-ēreš

carved an official record of the event into a clay tablet.

Although the event, which we know

today as the aurora borealis or northern lights, wouldn’t have affected the

course of nature at the time, it is now helping astronomers understand our Sun

and may even help protect astronauts and assets in space.

The Assyrian record is thought to

be one of the earliest known observations of aurorae, dating to around 660 BCE.

Aurorae are created by high-energy particles launched from the Sun, and

historical records offer a way to study conditions on the Sun long before the

invention of telescopes.

“Direct observations [of the Sun]

span some 400 years with sunspot observations, and ground-based instrument

observations are mostly within 200 years,” said Hisashi

Hayakawa, lead author of a new study and an astronomer at Osaka University

in Japan and the Rutherford Appleton Laboratory in the United Kingdom. “To

discuss the kind of less frequent, but more hazardous events [coming from the

Sun], we need to expand the data coverage, like with historical documents.”

Blasts in the Past

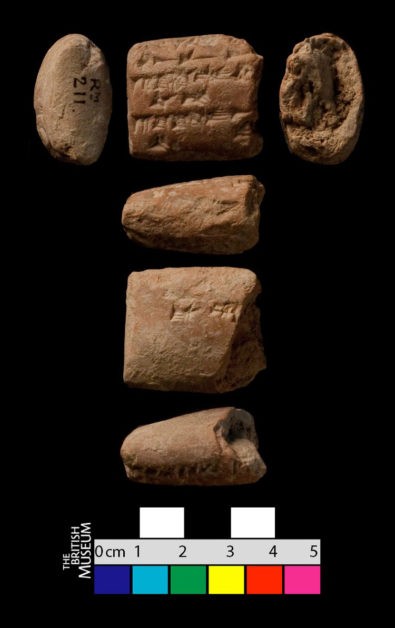

Hayakawa and his colleagues

identified the records by examining ancient cuneiform tablets held in the

British Museum. These tablets were carved by Assyrian court scribes, whose job

it was to document important happenings in the empire. They often included

accounts of celestial appearances, like comets (ṣallummû), meteors (kakkabu

rabû), and lunar and solar halos (tarbāṣu), which were thought to be omens of

the future. Although most Assyrian and Neo-Assyrian tablets aren’t explicitly

dated, their authorship gives scholars a close idea of when the tablet was

written—usually within a decade.

In the tablets studied,

researchers found two references from Nineveh (a city near current-day Mosul,

Iraq) and one from Babylon (built along Iraq’s Euphrates River) that describe

red aurorae, using terms like akukūtu, meaning “red glow,” or stating “red

covers the sky.” Using the authorship of the tablets, researchers think the

events happened sometime between 680 BCE and 650 BCE, a century earlier than

previous records of aurorae.

Documenting aurorae helps astronomers understand patterns of solar

activity. Magnetic storms on the Sun can release giant plumes and jets of

materials, some of which fall back into the Sun and some of which get ejected

and spewed across the solar system. Particles that make it to Earth can be

funneled along magnetic field lines into Earth’s upper atmosphere, where they

strike atmospheric particles, causing them to glow. Red aurorae, like the ones

seen in ancient Assyria, are typically caused by low-energy electrons.

Since they follow magnetic field

lines, aurorae are most commonly seen near the poles. But strong solar events can make aurorae visible at

lower latitudes. Although today it is rare to see an aurora in the Middle East,

2,000 years ago the magnetic North Pole was much closer to Mesopotamia,

hovering over the Norwegian archipelago of Svalbard instead of its current

location just 4° south of the geographic North Pole.

The newly identified records also

match indirect evidence of solar activity. Since 2012, several studies have

found isotope data of carbon-14 levels recorded in tree rings that suggest a

strong burst of solar activity during the same time period. By adding Assyrian

observational evidence to these natural archival data, scientists are better

able to confirm that the event was truly a space weather event

caused by an extreme solar storm.

“Comparing these data from

natural archives to real historical records made by contemporary astrologers at

the time is very important,” said Ilya Usoskin, a space physicist at the University of Oulu

in Finland who was not involved with the new research. “From it, we know that

we are on the right track, because the two records match each other.”

Dangerous Beauty

Although solar energetic

particles can create beautiful aurorae, they can also fry electronics in telecommunications

satellites and harm astronauts in space. The distance the ancient Assyrian

aurorae were seen from the pole is similar to an event in 1989 when the power

grid in all of Quebec was knocked out.

“It is likely that the [ancient]

storms were considerably large,” Hayakawa said. “Storms with similar intensity

[today] would be harmful to modern technological infrastructures.”

Understanding the historical frequency of solar storms and learning how

to predict such big events are important for mitigating their effects on our

tech-based society. The historical data can help astronomers model how often

such extreme events occur and better assess the probability of similar extreme

events happening again.

“Direct observations from the

last decades are not very useful here because they just cover too short period

of time,” Usoskin said. “Such historical records are very helpful because now

we know that during the last, say, 3,000 years there were three events of that

magnitude, which means that, on average, we may expect such disasters to occur

a few times per millennia.”

Hayakawa and his colleagues

recently presented their analysis of the Assyrian tablets in a paper in Astrophysical Journal Letters.

This Neo-Assyrian tablet from the Library of Ashurbanipal provided researchers with what may be one of the earliest descriptions of the aurora borealis. The Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

|