ishtartv.com- icr + crystalinks

Background

The Epic of Gilgamesh has been of interest to Christians

ever since its discovery in the mid-nineteenth century in the ruins of the

great library at Nineveh, with its account of a universal flood with

significant parallels to the Flood of Noah's day.1, 2 The rest of the Epic,

which dates back to possibly third millennium B.C., contains little of value

for Christians, since it concerns typical polytheistic myths associated with

the pagan peoples of the time. However, some Christians have studied the ideas

of creation and the afterlife presented in the Epic. Even secular scholars have

recognized the parallels between the Babylonian, Phoenician, and Hebrew

accounts, although not all are willing to label the connections as anything

more than shared mythology.3

There have been numerous flood stories identified from

ancient sources scattered around the world.4 The stories that were discovered

on cuneiform tablets, which comprise some of the earliest surviving writing,

have obvious similarities. Cuneiform writing was invented by the Sumerians and

carried on by the Akkadians. Babylonian and Assyrian are two dialects of the

Akkadian, and both contain a flood account. While there are differences between

the original Sumerian and later Babylonian and Assyrian flood accounts, many of

the similarities are strikingly close to the Genesis flood account.5 The

Babylonian account is the most intact, with only seven of 205 lines missing.6 It

was also the first discovered, making it the most studied of the early flood

accounts.

The Epic of Gilgamesh is contained on twelve large tablets,

and since the original discovery, it has been found on others, as well as

having been translated into other early languages.7 The actual tablets date

back to around 650 B.C. and are obviously not originals since fragments of the

flood story have been found on tablets dated around 2,000 B.C.8 Linguistic

experts believe that the story was composed well before 2,000 B.C. compiled

from material that was much older than that date.9 The Sumerian cuneiform

writing has been estimated to go as far back as 3,300 B.C.10

The Story

The Epic was composed in the form of a poem. The main figure

is Gilgamesh, who actually may have been an historical person. The Sumerian

King List shows Gilgamesh in the first dynasty of Uruk reigning for 126 years.11

This length of time is not a problem when compared with the age of the

pre-flood patriarchs of the Bible. Indeed, after Gilgamesh, the kings lived a

normal life span as compared with today.12 The King List is also of interest as

it mentions the flood specifically—"the deluge overthrew the land."13

The story starts by introducing the deeds of the hero Gilgamesh.

He was one who had great knowledge and wisdom, and preserved information of the

days before the flood. Gilgamesh wrote on tablets of stone all that he had

done, including building the city walls of Uruk and its temple for Eanna. He

was an oppressive ruler, however, which caused his subjects to cry out to the

"gods" to create a nemesis to cause Gilgamesh strife.14

After one fight, this nemesis—Enkidu—became best friends

with Gilgamesh. The two set off to win fame by going on many dangerous

adventures in which Enkidu is eventually killed. Gilgamesh then determines to

find immortality since he now fears death. It is upon this search that he meets

Utnapishtim, the character most like the Biblical Noah.15

In brief, Utnapishtim had become immortal after building a

ship to weather the Great Deluge that destroyed mankind. He brought all of his

relatives and all species of creatures aboard the vessel. Utnapishtim released

birds to find land, and the ship landed upon a mountain after the flood. The

story then ends with tales of Enkidu's visit to the underworld.16 Even though

many similarities exist between the two accounts, there still are serious

differences.

Conclusions

From the early days of the comparative study of these two

flood accounts, it has been generally agreed that there is an obvious relationship.

The widespread nature of flood traditions throughout the entire human race is

excellent evidence for the existence of a great flood from a legal/historical

point of view.20 Dating of the oldest fragments of the Gilgamesh account

originally indicated that it was older than the assumed dating of Genesis.21

However, the probability exists that the Biblical account had been preserved

either as an oral tradition, or in written form handed down from Noah, through

the patriarchs and eventually to Moses, thereby making it actually older than

the Sumerian accounts which were restatements (with alterations) to the

original.

A popular theory, proposed by liberal "scholars,"

said that the Hebrews "borrowed" from the Babylonians, but no

conclusive proof has ever been offered.22 The differences, including religious,

ethical, and sheer quantity of details, make it unlikely that the Biblical

account was dependent on any extant source from the Sumerian traditions. This still

does not stop these liberal and secular scholars from advocating such a theory.

The most accepted theory among evangelicals is that both have one common

source, predating all the Sumerian forms.23 The divine inspiration of the Bible

would demand that the Genesis account is the correct version. Indeed the

Hebrews were known for handing down their records and tradition.24 The Book of

Genesis is viewed for the most part as an historical work, even by many liberal

scholars, while the Epic of Gilgamesh is viewed as mythological. The One-source

Theory must, therefore, lead back to the historical event of the Flood and

Noah's Ark.25 To those who believe in the inspiration and infallibility of the

Bible, it should not be a surprise that God would preserve the true account of

the Flood in the traditions of His people. The Genesis account was kept pure

and accurate throughout the centuries by the providence of God until it was

finally compiled, edited, and written down by Moses.26 The Epic of Gilgamesh,

then, contains the corrupted account as preserved and embellished by peoples

who did not follow the God of the Hebrews.

REFERENCES

Keller, Werner, The Bible as History, (New York: William

Morrow and Company, 1956), p. 32.

Sanders, N.K., The Epic of Gilgamesh ,(an English

translation with introduction) (London: Penguin Books, 1964), p. 9.

Graves, Robert, The Creek Myths, Volume 1,(London: Penguin

Books, 1960), pp. 138-143.

Rehwinkel, Alfred M., The Flood in the Light of the Bible,

Geology, and Archaeology, (St. Louis: Concordia Publishing, 1951), p. 129.

O'Brien, J. Randall, "Flood Stories of the Ancient Near

East", Biblical Illustrator, (Fall 1986, volume 13, number 1), p. 61.

Barton, George A., Archaeology and the Bible, (Philadelphia:

American Sunday School Union, 1916), pp. 273-277

Keller, The Bible as History, p. 33.

Whitcomb, John C. and Morris, Henry M., The Genesis Flood, (Phillipsburg:

Presbyterian and Reformed, 1961), p. 38.

Heidel, Alexander, The Gilgamesh Epic and Old Testament

Parallels, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1949), p. 13.

O'Brien, "Flood Stories of the Ancient Near East",

p. 61.

Heidel, The Gilgamesh Epic and Old Testament Parallel, p.

13.

Sanders, The Epic of Gilgamesh, p. 21.

Vos, Howard F., Genesis and Archaeology, (Chicago: Moody

Press, 1963), p. 35.

Sanders, The Epic of Gilgamesh, pp. 20-23.

Ibid., pp. 30 39.

Ibid., pp. 39-42.

The Bible as History, p. 33.

Sanders, The Epic of Gilgamesh, p. 109.

O'Brien, "Flood Stories of the Ancient Near East",

pp. 62, 63.

Morris, Henry M., Science and the Bible, (Chicago: Moody

Press, 1986), p. 85.

O'Brien, "Flood Stories of the Ancient Near East",

p. 64.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Morris, Science and the Bible, p. 92.

Ibid., p. 85.

Whitcomb, John C., The Early Earth (Grand Rapids: Baker Book

House, 1986), p. 134; Whitcomb and Morris, The Genesis Flood, p. 488.

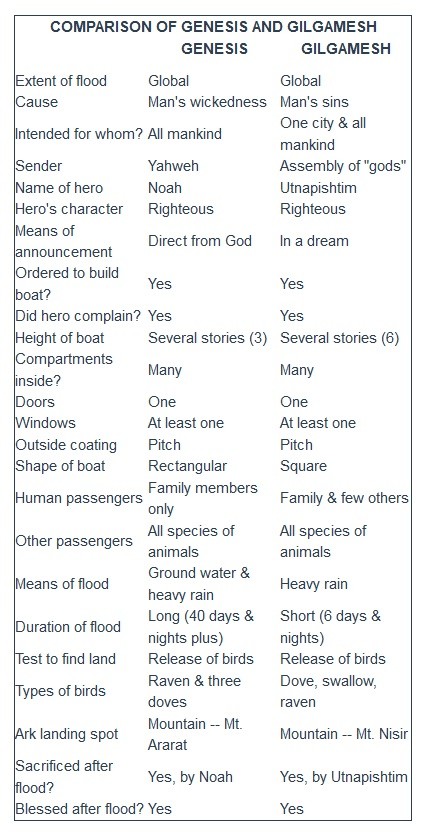

The table presents a comparison of the main aspects of the two accounts of the flood as presented in the Book of Genesis and in the Epic of Gilgamesh. Some comments need to be made about the comparisons in the table. Some of the similarities are very striking, while others are very general. The command for Utnapishtim to build the boat is remarkable: O man of Shuruppak, son of Ubar-Tutu, tear down thy house, build a ship; abandon wealth, seek after life; scorn possessions, save thy life. Bring up the seed of all kinds of living things into the ship which thou shalt build. Let its dimensions be well measured. 17 The cause of the flood as sent in judgment on man s sins is striking also. The eleventh tablet, line 180 reads: Lay upon the sinner his sin; lay upon the transgressor his transgression. 18 A study of these parallels to Genesis 6-9, as well as the many others, demonstrate the non-coincidental nature of these similarities. The meanings of the names of the heroes, however, have absolutely no common root or connection. Noah means (rest) while Utnapishtim means (finder of life). 19 Neither was perfect, but both were considered righteous and relatively faultless compared to those around them. Utnapishtim also took a pilot for the boat, and some craftsmen, not just his family in the ark. It is also interesting that both accounts trace the landing spot to the same general region of the Middle East; however, Mt. Ararat and Mt. Nisir are about 300 miles apart. The blessing that each hero received after the flood was also quite different. Utnapishtim was granted eternal life while Noah was to multiply and fill the earth and have dominion over the animals.

Noah s Ark Cycle: 3. The Flood, Kaspar Memberger (I)- 1588

The eleventh tablet of the Gilgamesh Epic, and describes how the gods sent a flood to destroy the world

|