An Iraqi worker excavates a rock-carving relief at the Mashki Gate, one of the entrances to the ancient Assyrian city of Nineveh, on the outskirts of Mosul. AFP

Ishtartv.com

– thenationalnews.com

Melissa Gronlund, Aug 21, 2023

Last year, a team excavating the

Assyrian-era gates to the ancient city of Nineveh, on the outskirts of Mosul,

found that the stone slabs used as foundations were actually exquisitely carved

reliefs; depicting archers, besieged cities and incredible likenesses of the

surrounding landscape.

Now, they are beginning the next

phase of work, exploring new areas for excavation and starting on the gate's

reconstruction. They will commission a new kiln to re-create the earthenware

bricks used by the Assyrians millennia ago, in a major capacity-building

project under Iraq's State Board of Antiquities and Heritage.

The team arrived in 2021 to

excavate the Mashki Gate after its Saddam Hussein-era reconstruction was

destroyed by ISIS. When they spotted the top of a carved figure of an archer

reaching out from what they assumed were stone foundations, they began digging

towards the bottom-most layer of the gate, which was built in 700 BC.

“It blew me away,” says project manager and

archaeologist Michael Danti, who is directing the dig with the Iraqi

archaeologist Fadhel Mohammed Khdir Ali of the SBAH. “On the lower 30 to 40cm

[of the reliefs] we have probably the best preserved portions of Sennacherib

reliefs anywhere – because they're pristine. They've never suffered from fire

damage or the elements. They’re really spectacular,” adds Danti.

The seven carved panels came from

the South West Palace – known as “the palace without rival” from its

inscriptions – that was established by the Assyrian king Sennacherib, a

prominent member of the Sargonid dynasty. Sennacherib, who ruled from 705 BC to

681 BC, made Nineveh his capital, raising it from a provincial town to a vast

metropolis.

The Mashki Gate reliefs bear

inscriptions from his reign on their reverse side, and match others from the

Palace in style and subject. Many of those panels, which were discovered during

the first excavation of the Nineveh in the mid-nineteenth century, are now in

the British Museum.

The reliefs depict Sennacherib’s

third military campaign, which was waged in the West against the Phoenicians

and the kingdom of Judah. Some show finely detailed archers, with tightly

curled beards, pulling back their strings as they prepare to launch arrows.

Others depict the landscape they fought in, with individually carved leaves,

their veins visible, or groves of small wooded trees.

Another relief, which like the

others, was carved in alabaster and would have originally been painted, shows

the encircled city of Lachish, which was captured by Sennacherib’s forces in 701

BC.

A moment of artistic flowering

Making the discovery even more

exciting is that Sennacherib instituted an important period of stylistic change

in Assyrian culture. “Unlike earlier rulers, who documented their military

successes in cuneiform inscriptions, Sennacherib only wrote a short inscription

on the back, attesting to the fact that he commissioned the reliefs, and let

the vivid depiction instead reveal his military prowess,” says Danti.

“Another innovation was his use of time among

the sequencing of the reliefs: rather than trying to encapsulate one moment

within one relief, he arranged them in sequences, so that the audience could

follow the story of the campaign.”

Like the South West Palace, the

original floor of the Mashki Gate dates back to Sennacherib. Over the

subsequent century, two further reconstructions were made that each added a new

floor. When the Babylonians sacked Nineveh in 612 BCE, they burned Mashki Gate,

which had been erected with baked bricks around a timber support. That left the

last of the three levels in a “Pompeii”-like state, with its fighters and their

weapons trapped inside.

It was this scene that was

excavated in the late 1960s by the Iraqi archeologist Tariq Madhloom, who has

also worked in the region of Mleiha in Sharjah. Madhloom recreated two walls of

the gate, which were then targeted as examples of the pre-Islamic past after

ISIS took over the Mosul region in 2014, and were entirely destroyed.

Still a mystery

The team, comprised of

archaeologists from Iraq and the University of Pennsylvania's Iraq Heritage

Stabilisation Program, have now been studying the reliefs for a year, but

questions remain. Why were these reliefs were used as a foundation? And instead

of going through the effort to chisel out the designs – Danti and his team also

found the shards of stone and, in one case, a 8th-century BC chisel itself –

why didn’t they simply plant them in the ground facing outwards, with their

blank backs creating the visible foundations for the gate? And who reused them?

Whoever installed the reliefs

tried to remove the depictions, hacking away at them with chisels. And because

these panels, like the others, have been preserved in the ground, the chisel

marks themselves look like they were made yesterday – so much so that reports

in local media alleged they had been made by ISIS.

The current working hypothesis is

that the pieces were moved during the reign of King Ashurbanipal, whose violent

reign helped hasten the decline of the Assyrian Empire. It is known that

Ashurbanipal constructed a new palace in Nineveh, and the dates between the

construction of the third level of the gate and the Ashurbanipal’s tenure

overlap. But this will have to be confirmed by further study, as the team – its

process halted by the discovery – continues its project of excavating down to

the original Sennacherib floor.

Future

The long-term plans for Mashki

Gate will be to partially reconstruct it, in order to show its historical

importance. Right now, the site for the Gate, which lies about 600 metres from

the Palace, are grassy, undeveloped fields, strewn with rocks and archeological

remains. Across the busy road from the site is eastern Mosul, the new town,

whose riverside cafes and restaurants buzz with the excitement of a city keen

to enjoy some peace and security.

Any reconstructions will go

forward with the buy-in of this local population, as the State Board of

Antiquities and Heritage treads lightly through the reconstruction.

The excavations elsewhere in

Nineveh are being undertaken by Italian and German archaeological teams, who

typically have more university funding for such expeditions than their US and

UK counterparts. Danti’s team is funded by Aliph and University of Pennsylvania,

and coordinated by the SBAH.

Whether the reliefs will remain in

place or go to a museum, in Mosul or elsewhere, is yet to be decided.

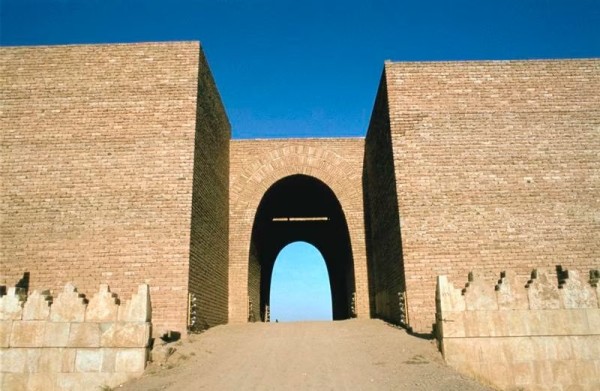

Pictured in 1977, Mosul's Mashki Gate was reconstructed during Saddam Hussein's time before being damaged by ISIS. Getty Images

A carved figure of an archer at Mashki Gate. Photo: Melissa Gronlund

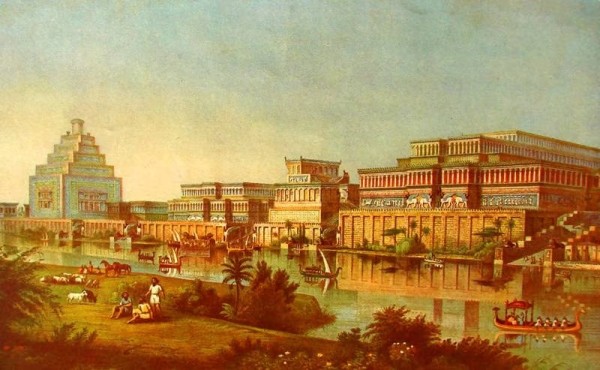

The city of Nineveh, with the Mashki Gate, depicted at the height of Assyrian power, when it was capital of the Neo-Assyrian Empire. Alamy

Iraqi workers excavate a rock-carving relief at the Mashki Gate, one of the monumental gates to the ancient Assyrian city of Nineveh. AFP

The reconstruction of the Mashki Gate as it stood before ISIS's destruction. Photo: Mohamed Al Baroodi

|